Garden State “Developers:” SEC Sues Real Estate Investment Firm and its Principals for $630 Million Fraud

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), in a Complaint (the “Complaint”) filed on Thursday, Oct. 13, 2022, in the Federal Court for the District of New Jersey, charged National Realty Investment Advisors LLC (“NRIA”) and four of its principals (Messrs. Rey E. Grabato II, Daniel Coley O’Brien, Thomas Nicholas Salzano, and Arthur S. Scutaro) with engaging in a nationwide campaign to sell interests in an NRIA-managed fund that purportedly would be used to buy and develop real estate properties. The Complaint also names Salzano’s prior wife and his current wife as Relief Defendants. According to the Complaint, the Defendants (i.e., NRIA and the four principals) raised approximately $630 million from some 2,000 investors during the period from February 2018 until January 2022. NRIA filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on June 7, 2022. The SEC alleges that those investor funds were only occasionally used to make real estate investments, and instead, were primarily used to:

- pay distributions to other investors (a practice sometimes characterized as “robbing Peter to pay Paul”);

- pay for Salzano’s personal and luxury purchases; and

- pay reputation management firms to (in the words of the SEC’s Oct. 13, 2022 Press Release [the “Press Release”] about this case) “thwart investors’ due diligence of the [individual Defendants].”

Thomas P. Smith, Jr., Associate Regional Director of Enforcement in the SEC’s New York Regional Office, is quoted in the Press Release as saying:

In classic Ponzi fashion, these defendants allegedly told investors that they would be paid distributions from profits of their fund when, in reality, payments were being made from the investors’ own funds. What makes this behavior even more callous is that they allegedly took advantage of 382 retirees who had contributed more than $94 million [from their] savings.

The victims, including the retirees, had been lured by promised returns of up to 20% on the funds they invested.

Charles Ponzi & the “Ponzi Scheme”

“Ponzi scheme” is a frequently heard sobriquet for a variety of fraudulent and illegal activities seeking to exploit the human predilection for “easy money.” But who exactly was Ponzi, and what did he do to become so frequently invoked?

Charles Ponzi was born into a poor family in Lugo in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy on March 3, 1882. Determined to better his prospects, on Nov. 15, 1903, Ponzi arrived in Boston on the SS Vancouver with (according to his own statements) $2.50 in his pocket (having gambled the rest of his savings away on the voyage). After a difficult few years in Boston and its environs, Ponzi moved to Montreal, Canada, and obtained a job as an assistant teller in the newly-chartered Banco Zarossi. Banco Zarossi was established to serve the part of the wave of new Italian emigrants to North America who came to Canada. After forging a customer’s check, Ponzi was convicted and sentenced to jail.

After his release from a Canadian prison, Ponzi returned to the U.S. There, he was convicted of smuggling illegal Italian immigrants into the U.S. and served two years in the Federal Prison in Atlanta. Upon his release in 1919, he returned to Boston and implemented a scheme to make money by trading in Postal Reply Coupons, which were used by international marketers to facilitate responses by consumers to make purchases. Ponzi would buy Italian postal stamps that were relatively inexpensive (due to material inflation) and trade them for much more valuable U.S. postal stamps, and thereby make a “fortune.” That is, indeed, what individual “investors” thought, so by 1920, “investors” were promised that their dollars would double every 90 days. Then, as the scheme grew, Ponzi “improved” the offer by promising a 50% return every 45 days. At this time, banks were paying 5% on customer accounts.

In January 1920, Ponzi founded the Securities Exchange Company, and by June 1920, it had received over $2.5 million from “investors” in New England and, ironically, New Jersey. By July, $1 million was coming in each week, which skyrocketed to $1 million each day, serving the Italian emigrant community, Boston’s “Brahmins” and, fascinatingly, over 75% of the Boston Police Department. But after questions arose about the actual returns and the financial “strength” of Ponzi’s enterprises, his affiliated bank failed, and the “investors” lost some $20 million.

On Nov. 1, 1920, Ponzi pled guilty to federal mail fraud and was sentenced to five years in prison, of which he served 3 ½. After release in 1924, he was immediately indicted by Massachusetts on larceny charges, and in the resulting litigation, the U.S. Supreme Court held that Ponzi did not face double jeopardy with the state charges. After three trials (one acquittal, one deadlock, and one conviction) Ponzi was sentenced to 7-9 years in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Released on bail, Ponzi fled to Florida, where he boarded a ship sailing to New Orleans and then Italy. He was caught in New Orleans, returned to prison, and after release in 1934, deported to Italy, where he died in poverty.

Ponzi was an inventive self-starter whose moral and ethical shortcomings eventually led to his downfall AND the financial devastation of the hopes of those who sought a higher yield than was offered generally in the market.

NRIA and the NRIA Partners Portfolio Fund

NRIA, headquartered in Secaucus, New Jersey (in the Meadowlands, near Giants Stadium), began in 2006 by building 1,100 rowhouses in Philadelphia and planned “major developments on the city’s waterfront” according to Anthony R. Wood’s June 22, 2022 article in The Philadelphia Inquirer, as well as looking to invest in real estate projects in northern New Jersey, New York City, and Palm Beach, Florida. The same article states that beginning in 2018, NRIA “launched a heavily marketed offering called the NRIA Partners Portfolio Fund [the “Fund”], trumpeting its largest developments – in Philly, where it owns a vast tract of waterfront property that remains unbuilt upon; Hudson and Bergen Counties [in northern New Jersey]; Brooklyn; and Palm Beach.” According to the Complaint, NRIA managed the Fund, which was to acquire equity interests in real estate owning limited liability companies, while NRIA was to act as developer of the real estate assets. NRIA was entitled to a pro rata share of distribution of any profits, as well as a management fee equal to up to 3% of the purchase price of each property.

Prior to 2018 NRIA had, as noted in The Philadelphia Inquirer article, been involved in developing investment properties in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Florida. Investors in these properties rolled their $80 million of investments into the Fund, receiving what the Complaint says were “millions of dollars of ‘bonuses’ (but no cash payments) between 2019 and 2021.” Investors in the Fund received membership units described in a Private Placement Memorandum (PPM) and were supposed to be “accredited Investors,” although given the aggressive marketing of investments in the Fund, it is highly unlikely that all were. For a discussion of what it means to be an accredited investor, see my Sept. 15, 2020 blog “‘Accredited Investor’: Regulatory Design, the Revised Definition, and the Unfinished Results.”

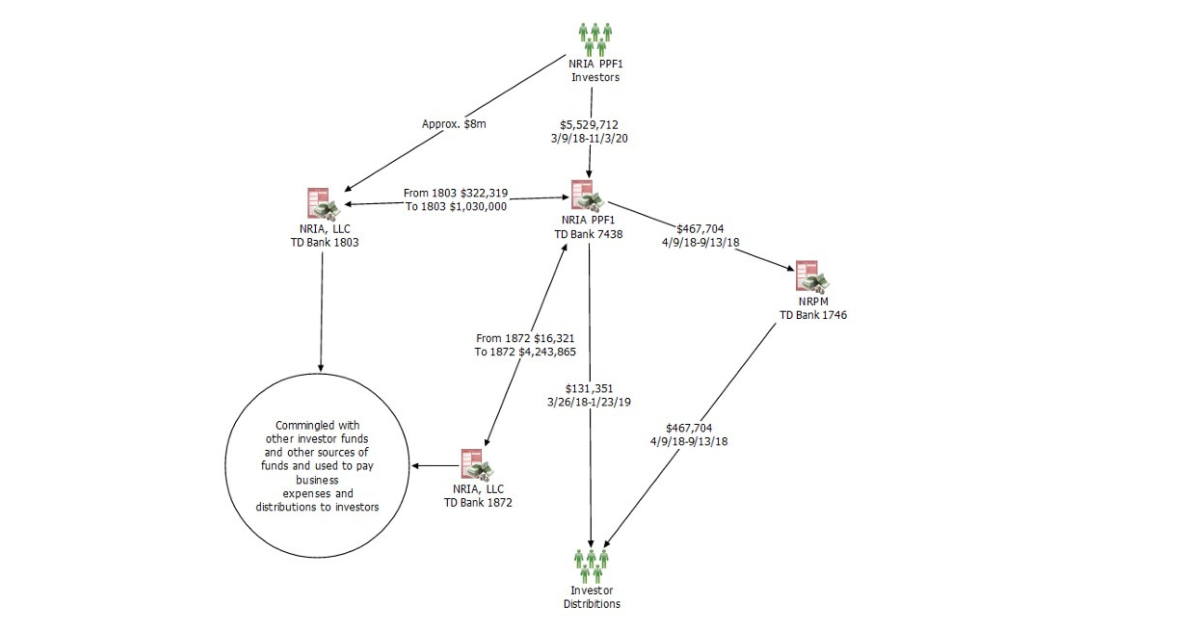

According to the Complaint, from its inception in 2018 through June 14, 2021, the PPM stated that “distributions were to come from the operating cash flow derived from investments made [in the entities in which the Fund invested].” The PPM claimed that “returns will be at least twelve percent annualized and that NRIA will pay any shortfall.” The Fund raised $630 million, but paid out only some $13.8 million in distributions. On page 10 of the Complaint, a fascinating graphic shows where monies actually went and follows up with a few startling examples:

- In May 2019 distributions reduced the NRIA cash account to a negative (-$29,000), which was brought positive by new investor payments and a loan;

- In October 2019 distributions reduced the cash account to negative (-$136,000), brought positive by two new investments totaling $290,000;

- In November 2019 distributions caused a negative balance (-$485,000) for a week, until new investments brought it positive.

Graph from (SEC VS. NRIA LLC, Grabato II, O’Brien, Salzano, Scutaro,& Budinska, and Samul, 2022)

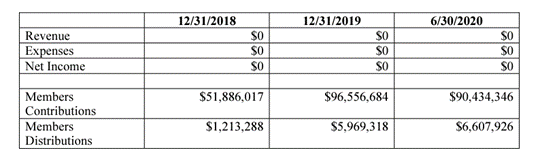

As shown in graphs on page 12 of the Complaint, neither the Fund nor NRIA had sufficient income to pay distributions at the levels the Fund was paying.

Graph from (SEC VS. NRIA LLC, Grabato II, O’Brien, Salzano, Scutaro,& Budinska, and Samul, 2022)

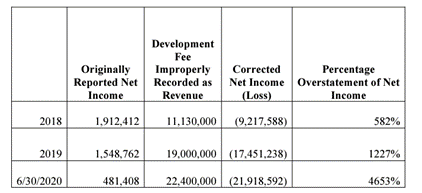

The SEC asserted that NRIA in the PPMs (five versions in the relevant time period) misrepresented revenue, income, and equity to the investors, particularly from using non-GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) financials such as recording development fees as revenue on contract signing, not on collection, as depicted on page 14 of the Complaint.

Graph from (SEC VS. NRIA LLC, Grabato II, O’Brien, Salzano, Scutaro,& Budinska, and Samul, 2022)

What neither NRIA nor the Fund bothered to tell investors was as noted at the outset: the monies were in fact used to pay enough distributions to keep investors interested, much as in Charles Ponzi’s scheme, and a great deal of the rest was used by the four individual Defendants for their own amusements and to conceal information about the unsavory background of some of them. So $1.2 million went to Salzano’s current wife (a Relief Defendant); some hundreds of thousands went to reputation management firms to conceal a Federal Trade Commission enforcement action against Salzano and Scutaro for defrauding consumers of $47 million in telephone and internet services from a company they ran AND use of those same firms to conceal Salzano’s conviction of five counts of theft in Louisiana resulting in a fine and three years of “supervised” probation; $4.2 million went to Grabato; $6.7 million to O’Brien; $640,000 to Salzano; and $260,000 to Salzano’s former wife (another Relief Defendant).

The Marketing and the End

All this time, NRIA was engaged in a “heavily marketed offering” of membership units in the Fund. Indeed, The Philadelphia Inquirer article reports that NRIA had “undertaken a major marketing campaign for the fund, spending an estimated $9 million on TV ads since the start of 2019. …It [also] plastered billboards at the entrances of the Lincoln and Holland Tunnels.” Having seen a number of those TV ads, each of which focused on photographs of impressive commercial and/or residential developments, I can attest to their seductive presentations. But much like Ponzi’s fate, all things came to an end once someone pushed hard to investigate the finances and operations of NRIA and the Fund; and the body that accomplished that was the New Jersey Bureau of Securities in the Division of Consumer Affairs in the Department of Law and Public Safety (i.e. the Attorney General’s Department). The Bureau, led by Acting Bureau Chief Amy Kopelton with the assistance of several Deputy Attorneys General, brought these miscreants to justice with the filing of a Summary Cease and Desist Order on June 21, 2022. I have a good understanding of this process, as I was the American Bar Association’s Liaison from the State Regulation of Securities Committee of the Business Law Section from August 1981 until the end of 2019 and served as the Attorney General appointed Chair of the Securities Advisory Committee to the Bureau from 1995 until 2001.

Aided by the investigative work of the Bureau, the SEC on Oct. 13, 2022, filed the Complaint charging the Defendants with the following: violation of Section 17(a) of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, for obtaining monies from the sale of securities using fraud; and Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, and Rule 10b-5 thereunder for using material misstatements and omissions to defraud investors in the sale of securities. In addition, the Relief Defendants were charged with unjust enrichment. The Commission seeks a permanent injunction against future violations of the cited securities laws; imposition of civil money penalties; disgorgement of ill-gotten gains plus pre-judgment interest; and a permanent bar against serving as an officer or director of a public company. The Commission also seeks disgorgement of ill-gotten gains plus prejudgment interest from the Relief Defendants.

In the last sentence of the Press Release, the SEC does manage to state that it “appreciates the assistance of the New Jersey Bureau of Securities.” So, a dedicated State regulator learning of the financial harm inflicted on those seeking higher yield when the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System was holding interest rates close to zero, carried out its sworn duty “To Serve, and Protect.”

If you have any questions concerning this post or any related matter, please feel free to contact me at pdhutcheon@norris-law.com.