Court Affirms That Children Cannot Sue on Behalf of a Parent Solely by Virtue of Being the Parent’s Child

A recent court decision stating that children do not have the legal standing to sue on behalf of their parents, simply by being their child and closest family member, reiterates the need for older parents and their adult children to engage in basic planning for the possibility of the parent experiencing a loss of capacity, or even diminished capacity, which could leave the parent vulnerable to exploitation. The case involved a father, his daughter, and the father’s long-time significant other. The father owned a business that employed his daughter. As the father aged, the daughter became increasingly involved in the management of the business. In late 2016, the father was hospitalized after falling and there was evidence that during this time, his cognitive abilities declined. In early 2018, he suffered a stroke. Throughout these medical events, the daughter continued to manage the father’s business.

Shortly after the stroke, however, the significant other appeared at the business with a power of attorney purportedly signed by the father in 2017 (when he was recovering from the first hospitalization), demanding that the daughter vacate the premises. Under the authority of the purported, suspect power of attorney, the significant other took over management of the father’s business and prevented the daughter from having any further involvement.

Children Cannot Sue on Behalf of Parent

The daughter then filed a lawsuit on behalf of her father, demanding that the significant other restore possession and control of her father’s business to her. The daughter focused on the power of attorney, which was executed under suspicious circumstances, and which, according to the handwriting expert that the daughter retained, was not genuine.

After a year of litigation (and presumably a year’s worth of counsel fees, not to mention fees for the handwriting expert), the court dismissed the daughter’s case At first, this may seem like a harsh result – was trying to help her father, and after all, she had been working at the business (her father’s business) until the significant other showed up out of the blue. And what about that suspect power of attorney?

The court ruled that a child has no legal basis (or “standing”) to sue on behalf of a parent solely by virtue of being the parent’s child. In this case, the daughter was not his agent under any power of attorney, she was not his guardian, and she had no formal role in the business other than as an employee terminable at-will. Because she had no right to bring the suit, to begin with, the validity of the significant other’s power of attorney was irrelevant.

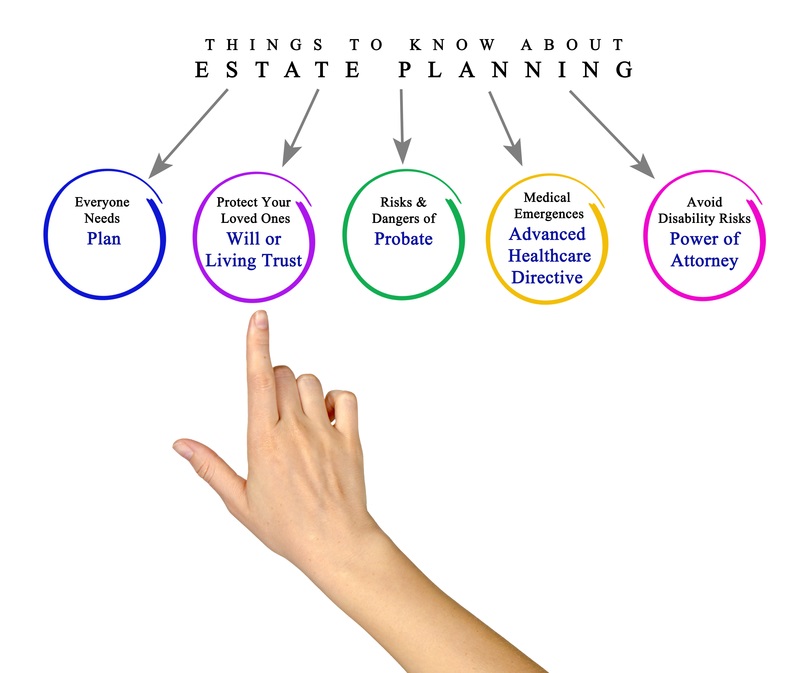

Advance Planning Can Avoid Confusion

The daughter can still choose to bring a second suit to be appointed as her father’s guardian. While this might ultimately get her the relief she wants, it likely will not come without a fight, as the significant other will probably claim that she, and not the daughter, should be the guardian Both cases (the case that was dismissed and the guardianship matter likely to be filed) could have been avoided, or at least made simpler for the daughter, had the father planned ahead. For example, she could have executed a power of attorney long before any issue of capacity arose, making it clear who he wanted to act for him. While a power of attorney is revocable, it could have required that the daughter be given advanced notice of any revocation, possibly making it more difficult for the significant other to secure a new power of attorney under what might have been questionable circumstances. A power of attorney can also indicate the principal’s preference as to who should be appointed as their guardian if one is ever needed.

As to the ownership and operation of the business, the father could have transferred his ownership interest in the business to a trust, with his daughter as trustee. This would have prevented the significant other (or anyone else) from taking control of the business merely with a power of attorney (and even if the trust were revocable, it at least would have required notice to the daughter). If the father was not comfortable giving up control of his ownership, he and his daughter could have entered into an employment agreement. An employment agreement would confer rights on the daughter that she could enforce in court, rather than leaving her as an at-will employee terminable for no cause. For example, it could limit the circumstances under which she could be terminated, which could have prevented the significant other from pushing her out for no apparent reason other than, due to the suspect power of attorney, she could do so.

Granted, this all assumes that the father truly wanted his daughter (not his significant other) to take over and that the significant other may have gotten away with something (at least for the time being). Or it may be true that nothing improper took place. But that is exactly the point. When these types of questions are left completely unanswered (by the father’s failure to plan), courts are left to make their best guess to determine what someone in the father’s position would have wanted, and there is increased potential for improper conduct. Simply being the child and closest family member of an older parent may not give you standing to sue on behalf of or protect the parent’s interests in court, so make sure to have the tough conversations about who your parent wants to step in should the need ever arise.

If you have any questions about this post or any estate planning and administration matters, please feel free to contact one of our estate planning and administration attorneys.